Ham Radio Tech: Choosing a Portable Vertical Antenna that Matches Your Needs

Whether you’re a seasoned ham or buying your first antenna, choosing the right one is more about how you operate as an individual and less about the antenna’s capabilities. In previous OnAllBands articles, I’ve explored field antennas and the decision-making process behind choosing the right one. I believe that a practical understanding of your operating style is key to making the best choice.

This article is about vertical antennas—specifically, those designed to be portable and stealthy. These antennas are ideal for field operations like POTA, SOTA, or IOTA, and for those living under HOA restrictions that prohibit permanent antennas.

There are hundreds of vertical antennas on the market, and it’s beyond the scope of this post to cover them all. Instead, I’ll focus on three models I’ve personally used, each representing different concepts and reasons why you might choose one over another.

All of these antennas are multi-band, and while some can be installed permanently with proper sealing, they are primarily designed with portability and ease of setup in mind.

Before diving into the specifics, consider these questions as you search for your next antenna:

- What modes and power levels do you intend to operate? Ensure your antenna can handle the wattage and duty cycle of your chosen mode (SSB, CW, Digital). For example, an antenna that handles 100 watts SSB may not be suitable for 100 watts FT8.

- What bands do you plan to operate? Confirm that the antenna covers your preferred bands. Portable verticals are effective on 20 meters and above but become less efficient at lower frequencies due to the need for loading coils to electrically lengthen the radiating element. This compromises performance and decreases operating bandwidth. However, I’ve had great success on 80 meters with some portable verticals, though they are less efficient compared to longer wire antennas.

- How far do you plan to hike with this antenna? Check the specifications for weight and element lengths, as these factors will impact your comfort and the feasibility of carrying it in your pack.

- How important is frequency agility? If you primarily operate FT8 and stay on one frequency for extended periods, any antenna will likely suffice. If you frequently move across bands to chase activators or DX, consider an antenna that doesn’t require manual tuning.

***

Three Types of Portable Verticals

Here are three vertical antennas I’ve used in the field, along with their pros and cons:

***

1. Quarter Wave Verticals

One of the simplest vertical antennas is the quarter wave. My first quarter wave antenna was a 5-meter radiator wire (one-quarter the length of 20 meters) with four counterpoise wires on the ground. I attached the radiator to the center of my coax and the counterpoises to the shield. I’ve deployed the radiator vertically in a tree (great for permanent setups) and supported it with a fiberglass telescoping fishing pole (ideal for portable use).

While these antennas are simple to build, I prefer an antenna that works on multiple bands and is easy to deploy and pack. This is why I’m a big fan of the Chelegance MC-750 .

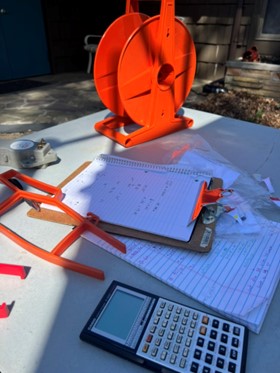

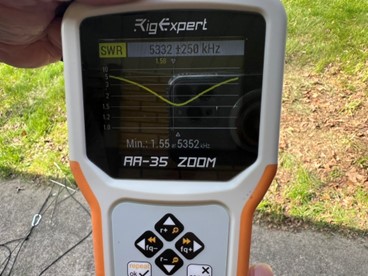

The MC-750 is a portable vertical deployed using either a stainless ground spike or a tripod. The vertical element is a stainless steel whip with silk-screen markings that help you deploy the antenna for resonance on multiple bands.

When I follow the silk-screen markings and all four counterpoise wires (attached to the base), I consistently achieve a near 1:1 SWR. Thus, no ATU is needed. The SWR remains consistent across various topographies.

The MC-750 ships with a coil for 40 meters. Chelegance also offers an optional 80 meter coil as well.

- Pros: Easy deployment, high quality, efficient, multi-band use with no ATU needed, resonates on 20-10 meters and 40/80 meters with coils, comes with a custom padded carrying case.

- Cons: Not truly a con, but you must adjust the whip length when changing bands if not using an ATU.

***

2. Verticals with Transformers

If you regularly use an antenna tuner in the field, you might prefer a high-quality multi-band vertical antenna equipped with a transformer to reduce potentially high impedances to a level manageable by most tuners. I think of this type of antenna as the vertical equivalent of a random wire antenna. Many of my QRP transceivers have internal ATUs, making this type of antenna very appealing. The one I have the most experience with is the Chameleon CHA MPAS Lite.

Like the MC-750, the MPAS Lite uses a stainless steel whip but includes a transformer at the base, making it easier to match the antenna across multiple bands with virtually any ATU. Additionally, it can operate on lower bands, including 80 meters, without needing a loading coil attached. While not as efficient below 30 meters, it remains highly effective for both POTA and SOTA where you are often the DX.

The MPAS Lite offers excellent frequency agility, which is a major advantage if you frequently hunt or chase other stations in the field. Just change the frequency, activate the ATU, and you’re set.

The MPAS antenna can also be configured as an end-fed random wire using the counterpoise wire. Consult the MPAS Lite manual for multiple configurations.

- Pros: Easy deployment, high quality, multi-band use, frequency agility, only one counterpoise, versatile platform for multiple antenna configurations.

- Cons: Pricier than the MC-750.

***

3. Loading Coil Verticals

I’ve used several antennas with helically wound coils and a sliding tuning coupler at the base to match the antenna across multiple bands. The coil at the base shortens the antenna electrically, making it portable and low profile—ideal for stealthy use or in neighborhoods with aggressive HOA restrictions.

Among the many coil antennas available, the new REZ Antenna Systems Ranger 80 stands out for its robustness. I was impressed with its ease of setup, high quality, and smooth tuning coupler. The REZ Ranger 80 antenna also handles higher power than other coil systems—100 watts CW/digital and 200 watts SSB.

The Ranger 80 is quick to deploy and incredibly durable. While I’ve never been a big fan of verticals with loading coils and sliding tuning couplers, as they can be finicky to tune, I found the REZ Ranger 80 to be the best of the bunch and more forgiving than others I’ve used.

- Pros: Easy deployment, superb quality, higher power handling capacity, multi-band resonance, no ATU required.

- Cons: Heavier than other options, tuning coupler needs adjustment for each band change, pricey.

***

Summary

Choosing the right portable vertical antenna is more about matching your equipment to your specific operating style than simply selecting the most capable model. Whether you prioritize ease of deployment, frequency agility, or power handling, the antennas discussed—like the Chelegance MC-750, Chameleon CHA MPAS Lite, and the REZ Ranger 80—offer distinct advantages that cater to different needs.

Before making your decision, consider the nature of your operations. Are you regularly chasing signals across multiple bands, or do you prefer to set up and stay on one frequency? Do you need a lightweight, portable solution for long hikes, or are you more concerned with stealth and ease of use in restricted environments? Your answers will guide you to the right antenna.

Ultimately, the best antenna is the one that enhances your enjoyment of the hobby, allowing you to operate confidently and efficiently in your chosen environment. If possible, try before you buy—borrowing from friends or club members can provide valuable insights that specs alone can’t offer.

The post Ham Radio Tech: Choosing a Portable Vertical Antenna that Matches Your Needs appeared first on OnAllBands.

At about 1.5 inches square, it’s easy to hang a Tile on your keychain, pop one in your checkbook and stash one in your wallet or purse. Load the Tile application on your Android phone or iPhone and you’re in business!

At about 1.5 inches square, it’s easy to hang a Tile on your keychain, pop one in your checkbook and stash one in your wallet or purse. Load the Tile application on your Android phone or iPhone and you’re in business!