Ham Radio Contesting for Techs? Yes, You Can!

Feeling left out? It’s a fact that most contests take place on the HF bands, but even as a Technician you can participate.

For starters, you only need your Technician license and a VHF and/or UHF FM handi-talkie—two things you already have. An HF transceiver covering 80-6 meters will give you even more opportunities

Contesting on the VHF/UHF Bands

The problem with the VHF bands is that they are often underutilized. But you can be sure someone will be on the air during a VHF contest weekend. Events like these increase activity and bring people out of the woodwork. A VHF contest is more like a friendly reunion of VHF enthusiasts—some you’ll know, others you’ll get to know.

If you only have FM gear, you will be at somewhat of a disadvantage. But you may still be able to work a bunch of stations. Hams have actually won their state in the ARRL VHF/UHF contest FM category with an HT and a good antenna. There are many more operators, with basic setups, that have fun and use the experience to become better operators.

In 2016, the ARRL contests allowed the use of the 2M FM calling frequency, 146.52 MHz. Note that the CQ Worldwide VHF Contest prohibits the use of 146.52 MHz. If the calling frequency gets busy, move off to any of the other standard simplex frequencies. The FM calling frequencies for the other VHF/UHF bands are 52.525 MHz and 446.000 MHz.

Perhaps you have one of those HF rigs that also does VHF, such as the ICOM IC-705, IC-706, Yaesu FT-818, FT-857, FT-991A, or FT-100D (otherwise known as a “shack in the box”). Most of the operation will be on 6 meters and 2 meters (mostly on the SSB portion of the band), with less activity on higher bands. Standard SSB calling frequencies are 50.125 MHz and 144.200 MHz.

In recent years, FT8 has been used extensively during VHF contests, mostly on 6 meters. This requires a bit more setup and configuration than operating voice, but the weak signal performance of FT8 is worth the effort. If you have experience with FT8, you should try it out on the 6M band during a contest. You may also encounter some FT4 activity as well.

Worldwide DX is not very common. But with good conditions, stations hundreds of miles away can be worked via tropospheric ducting, E-skip, and perhaps even meteor scatter. But weird things do happen. During 6-meter openings, multiple-hop sporadic E propagation has produced contact distances of up to 6,200 miles. Witnessing such an event is fascinating and mind-boggling, not to mention the adrenaline rush.

Get in the car and drive to increase your effective range. A rover is a mobile station that travels during a contest to activate locations, usually grid squares, during a contest. Rover stations are common in VHF contests, and often involve setups that can activate multiple bands from high places. Remember that VHF/UHF are usually line-of-sight modes, so you’ll want to go for high elevations with the fewest obstacles between you and your intended contacts. Mobile stations must indicate each location they are operating from on their log sheets.

Whether you’re roving or at home, most SSB/CW/Digi operation on VHF uses horizontal antenna polarization. A Yagi or dipole antenna with radiating elements parallel to the ground produces a horizontally polarized signal.

Technician Privileges on the HF Bands

Many hams forget that Technicians have HF privileges on CW. As the solar cycle reaches its peak, you’re likely to find more and more opportunities for nationwide and DX contacts on 80, 40, 15, and 10 meters. There’s a lot of activity on those bands, especially during domestic contests like the ARRL November Sweepstakes or the North American QSO Party.

Not a CW fan? You can operate SSB on 28.300-28.500, and other modes like digital, on this large chunk of ham real estate. With the peak of the solar cycle just ahead, this is an excellent time to explore the band. It’s primarily active from daytime to dusk.

Another way to participate is to be one of the operators in a multi-operator setup. As long as one of the operators with a General Class or Extra Class license acts as the control operator, you can operate in those portions of the bands where you don’t have privileges. Field Day can also allow you to try the HF bands. One local club uses State QSO Parties several times a year as an on-the-air practice at its club station.

These events are open to U.S. amateurs of all license classes and are a great way for Technician Class hams to compete in contests.

Contests

Here’s a small sampling of contests available on bands which Techs have privileges.

VHF/UHF Events for Technicians

VHF/UHF contests are often held during the summer and fall when propagation is best, but you’ll find some during other seasons as well.

- EOTA (Everyone On The Air) is sponsored by the Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, Amateur Radio Club. Held in September (it’s over for this year), EOTA is a local mini-version of POTA (Parks On The Air). Bands and modes—FM: 2M, 70cm, 6M; SSB: 6M and 10M. Look for local clubs that are sponsoring similar Tech-friendly events in your area.

- ARRL September VHF Contest is held the second full weekend in September. All amateur frequencies and modes above 50 MHz may be used.

- The ARRL January VHF Contest is held the third or fourth full weekend in January, as announced (January 18-20, 2025), for U.S. and Canadian stations.

- The CQ World Wide VHF Contest is held the third weekend of July. It promotes VHF activity on the 6- and 2-meter bands, and participants come from many countries around the world.

- Maine 2 Meter FM Simplex Challenge, held in March, is a ham radio contest primarily designed to give 2-meter operators a chance to compete on an even basis and have fun doing it.

- Central States VHF Society Spring Sprints are held in April and May. They’re band-specific with separate days/times for 50 MHz, 144 MHz, 222 MHz, 432 MHz, and Microwave.

HF Events for Technicians

HF contests, especially QSO parties, are a good training ground for general operation and Field Day. Remember, you have privileges on the following:

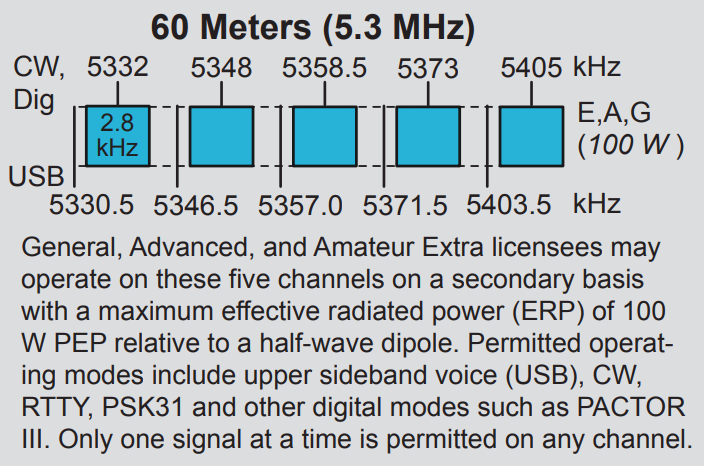

- 80, 40, 15 meters – CW only

- 6 meters – SSB/CW/Digital/AM/FM

- 10 meters – SSB/CW/Digital/RTTY

- North American QSO Parties are favorites of beginners and seasoned operators alike. The NAQPs are low-power only (100W or less), giving everyone less interference on the bands. CW is the second full weekend of January and the first full weekend of August. SSB is the third full weekend of January and the third full weekend of August.

- ARRL November Sweepstakes involvesstations in the United States and Canada (including territories and possessions) exchanging information with as many other U.S. and Canadian stations as possible on the 160, 80, 40, 20, 15, and 10M bands.

- CW: First full weekend in November (November 2-4, 2024)

- Phone: Third full weekend in November (November 16-18, 2024)

- State/Province QSO Parties can be a good way for new participants to get involved in the hobby. They can also be a break from the longer, more intense major contests. WA7BNM provides a comprehensive list with dates, times, and information links.

- ARRL 10-Meter Contest: With the contest going, you should hear lots of stations from late morning until about sundown. CW and Phone are the second full weekend of December (December 14-15, 2024).

- ARRL Field Day is the most popular on-the-air event held annually in the U.S. and Canada. On the last full weekend in June, more than 35,000 radio amateurs gather with their clubs, groups, or friends to operate remotely. Is it a contest, PR event, or emergency exercise? You can make a case for all three.

It Isn’t All About Winning

It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s about getting involved. You may never win the top place in a contest, but you’ll enjoy the competition, the camaraderie, and the experience you’ll gain as an amateur radio operator. Give it a try. A reference, ARRL’s Amateur Radio Contesting for Beginners, can help you on your way.

The post Ham Radio Contesting for Techs? Yes, You Can! appeared first on OnAllBands.